Child Be Free: A Prayer

“There is never a time in the future in which we will work out our salvation. The challenge is in the moment; the time is always now.”

-James Baldwin

“Funk not only moves, it can re-move, dig?’

-George Clinton

Let this be a temporal bridge. Let this be an unfurling of truncated lineage. A witness to invocation, to summoning, to seance. Let Child Be Free live as a meditation—a chant disguised as a collection of thread, wax, and hue. Allow this moment to be an opportunity to bear witness. Wear the heavy robe of history and be unafraid of its weight.

Child be free.

Child be free.

Child be free.

In creating this body of work, I felt an urgency to pay close attention to the dialogue between what is seen and what is erased, what is remembered and what is forgotten; to make visceral the tension between powers that sought to impose narratives on Black bodies and the quiet resilience that persists in the fissures of a collective memory. The discordance that lies where forces intent on eradication through systematic erasure meet the pure and profound unwillingness to be expunged.

The first time I opened one of the old ledgers from Roanoke County, its mass was not just physical. These books, resting in the courthouse, hold a world built on the backs of Black bodies, lives reduced to property and figures and material goods like spoons and livestock and furniture. As I turned the pages, I couldn’t help but notice the penmanship—each letter, each stroke, so meticulous, so beautiful in its precision. There was a strange dissonance in that beauty, a script that had clearly taken time to perfect, now used to document human lives in the coldest of terms. To my son Joshua I leave 2 negro girls and their increases forever. Forever. A mighty long time.

Child be free. Child be free. Child be free.

Increase—a clinical, detached reference to human reproduction within the context of ownership. A moment of realization: according to these records, I myself am an “increase.” I am defined, in some sense, as the expansion of a system that sought to control and erase my humanity. I understood then how deeply these systems of oppression were embedded, not just in history, but in my own existence. These ledgers, once tools of erasure, became mirrors reflecting the way these systems persist, how they’ve shaped not only the past but our present reality. My work became a way of confronting this inheritance, of rewriting it, of finding new ways to acknowledge and reclaim these histories through a process of deliberate, careful deconstruction.

Child be free.

Funny thing, time. That thing that runs through our fingers like water yet we swear is a solid, straight line. That thing which—despite all its perceivable behaviors—we trick ourselves into believing is a predictable variable. Perhaps our temporal perception is strictly a product of evolutionary necessity. How we move through our days is marked by experiences that occur in durational reference to places, objects, and people. And yet, the ledgers tell a different story. They remind us that time is far from linear. It folds, twists, and lingers. The people recorded in those ledgers are frozen in a temporal stasis, tethered to a past that refuses to let them go, even as we, their descendants, try to move forward. It is this fluidity of time, its refusal to conform to our expectations, that haunts me in this work. I wanted to disrupt that stasis and build a bridge across the temporal divide, connecting the past to the present, the ledger to the living.

Child be

free.

These ledgers were more than relics; they held lives—Black lives—reduced to entries, abstracted into the language of capital. The births and deaths of enslaved people were meticulously recorded, but their humanity was not. These were not individuals in the eyes of the record keepers; they were units of production, marked not by their joys or sufferings but by their utility to others. It is this erasure of humanity that Child Be Free seeks to resist. My practice, as it has evolved, meditates on this very tension: the external structures that impose limitations on identity, and the internal, ancestral, and spiritual lineages that offer a path toward transcendence.

The next phase of this project began with my engagement with the African American Vernacular Photos in the CSSR archive at Roanoke College. These images offered an antidote to the erasure I encountered in the ledgers. Here were faces—faces full of life, expression, and individuality. They were captured not as property but as people, and through their representation, they offered a powerful counter-narrative to the dehumanizing calculus of slavery. The photographs, though seemingly unrelated to the names in the ledgers, spoke to me of continuity, of the possibility that the individuals in these images could be connected to those unnamed in the historical records. This connection became central to the work—an attempt to build a threshold between the commodified and the free, between erasure and reclamation.

Child be free.

Child be free.

Child be free.

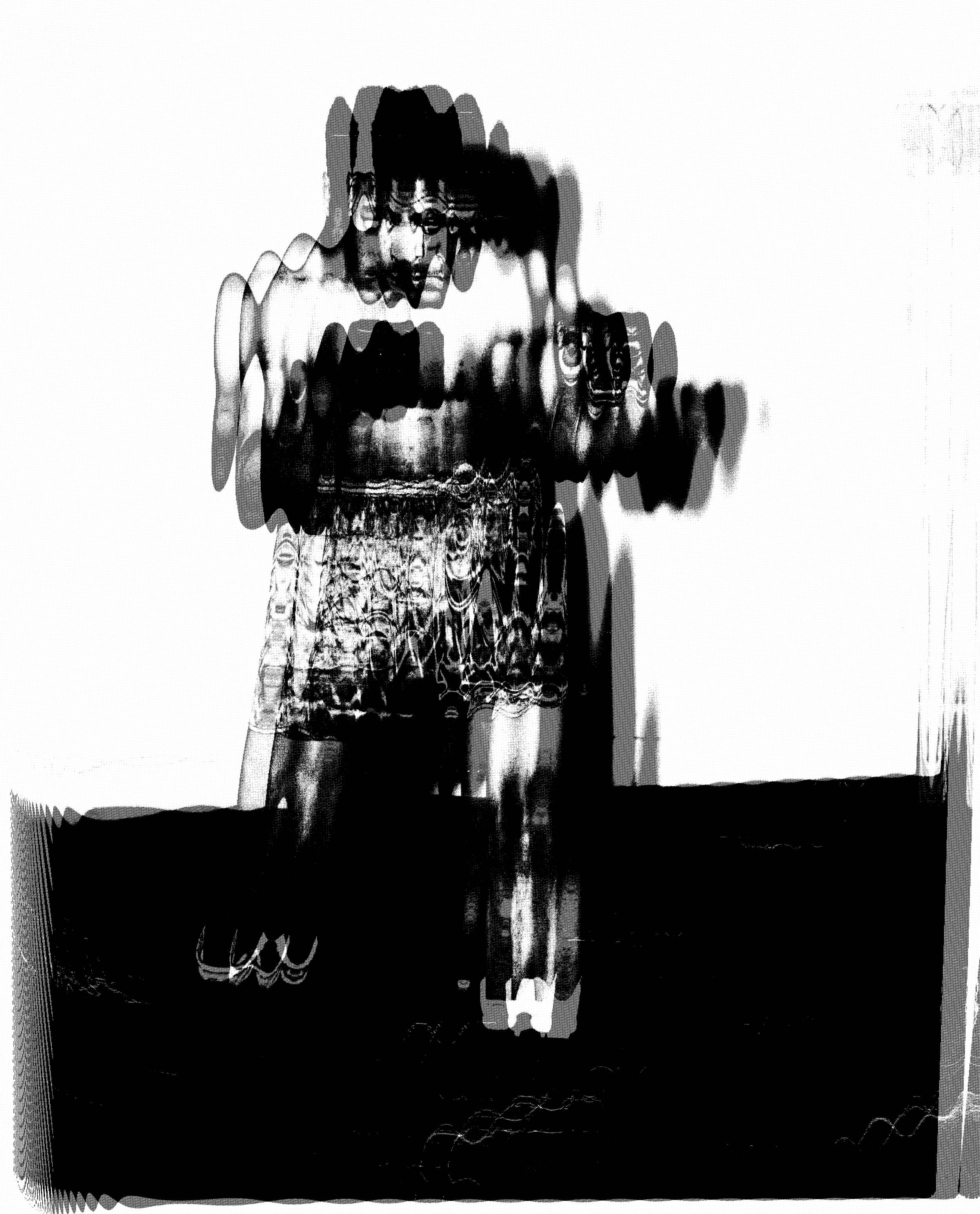

The repetition of these images within Child Be Free is no accident; it functions as a form of chant, a prayer in visual form. The act of repeating, retelling, and reimagining ferments the necessity for transformation. Through this recursive process, we can reclaim our own narrative, freeing both ourselves and our ancestors from what was imposed; that which sought to build a tesseract of oppression, reaching its hands into dimensions not yet seen. Each iteration of the image is a summoning—a way of carving out space for the individuals captured in the photographs to live beyond what was given and a portal through which those of the past can transcend.

The process of bringing these photographs into my work required more than simply reproducing them. It required a new way of thinking about medium and materiality, one that reflected the complexity of the themes in which I was engaging. I began by laser engraving the images onto canvas, a method that allowed for both precision and permanence, transforming the archival into the tangible. This step was more than a technical process; it was a deliberate act of preservation. Through this etching, I was ensuring that these lives—these stories—could not be erased again. The layering of wax onto the canvases introduced a rigidity that symbolized the fortification of memory, a protective layer to shield against the erosion of time.

What followed was an improvisational approach—an expansion of my practice into the tactile, the multi-dimensional. I began stitching the canvases together, embracing the tradition of quilt-making as an act of reconstruction. In this stitching, I found not only a metaphor for reconnecting the fractured lives represented in the photos and ledgers but also an act of resistance. Quilts, in Black American history, have long been more than functional objects; they are repositories of memory, symbols of resistance, maps to freedom. In Child Be Free, each stitch, each layer, is a reclamation of agency—a way of asserting that these lives, these individuals, are whole, complex, and free.

In the end, Child Be Free is a call to witness. To witness is not a passive act; it is to engage deeply with the stories and lives that have shaped us, to take responsibility for carrying them forward. With witnessing comes a responsibility to recall, and in that recollection lies an imperative to do so accurately; a holistic consideration. The faces in these photographs, the names in these ledgers, ask something of us: to see them, to recognize their humanity, to acknowledge that their lives were more than just entries in a book or moments captured on film. They were, and are, part of the ever-expanding continuum of Black life.

Child be free.

Johnny Floyd

Atlanta, GA

September 2024